Could a solar storm turn our world upside down?

In May, a particularly vivid aurora borealis set the night sky aflame and Instagram and TikTok alight. The stunning displays of red, green and purple shimmering lights, which are normally only witnessed in the polar regions, were seen across the US, Europe and as far away as Mexico, Italy and the Caribbean.

The amazing display was due to a geomagnetic superstorm so big that only a handful occur every century. That was followed a few days later by the biggest solar flare in seven years. The eruption was classified as an X8.7, just about the most powerful you can get on the solar weather scale.

The reason we’ve been treated to these unforgettable natural light displays (with more likely on the way) is that the sun is reaching the zenith of its 11-year cycle, and the solar maximum should hit sometime between now and 2025.

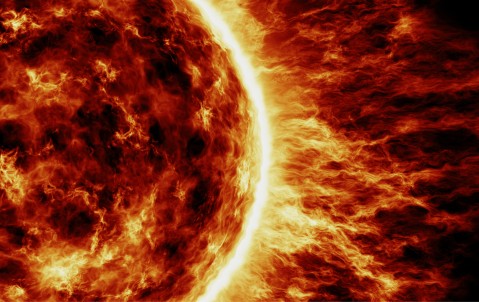

These spectacular solar storms occur when eruptions of energy and charged particles from the sun hit Earth’s geomagnetic field. “Sunspots can release solar flares or more powerful Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs), huge eruptions of energy that can travel between 250 km/second to as fast as 3000 km/s, meaning that a CME can reach our planet in as little time as 15 to 18 hours,” says Pascal Lecointe, Space Line Underwriter at Hiscox London Market.

“Sunspots can release solar flares or more powerful Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs), huge eruptions of energy that can travel between 250 km/second to as fast as 3000 km/s, meaning that a CME can reach our planet in as little time as 15 to 18 hours,” says Pascal Lecointe, Space Line Underwriter at Hiscox London Market.

Sun-weather watchers watch sunspots in the same way as hurricane forecasters will keep a close eye on sea temperatures and wind conditions in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific, to predict the upcoming storm season. Why? Because solar storms can have a big impact on us.

Most of us don’t know there’s weather on the sun or that it could affect us here on Earth. A glimpse of sunshine encourages us to dust off our barbecues and pressure wash our garden loungers, but the sun isn’t benign. It’s essentially “an enormous thermonuclear bomb”, a volatile seething ball of gases that can erupt with serious consequences for us.

Blowing a fuse

Solar storms are a regular occurrence that have had affected our power and communications systems in the past. In 2017, two huge solar flares disrupted GPS navigation systems, while another in 2011 played havoc with China’s radio communications. In 1989, Quebec’s entire electricity grid was knocked out for nine hours by a solar flare.

There are fears that the massive pulses of energy sent out by solar flares or CMEs could damage or even disable the thousands of satellites in space on which we rely in our daily lives for everything from online banking to the traffic lights.

But that fear is overstated, says Lecointe. “Although some of the smaller, cheaper ‘cubesat’ satellites could be disabled, most of the others are designed and built to withstand the effects of a solar flare or CME, in the same way that large ships are designed to weather storms on the high seas.”

“Although some of the smaller, cheaper ‘cubesat’ satellites could be disabled, most of the others are designed and built to withstand the effects of a solar flare or CME, in the same way that large ships are designed to weather storms on the high seas.” says Lecointe.

Starlink, the satellite arm of SpaceX which dominates the satellite internet market and which has 5601 satellites in operation at the time of writing, shrugged off May’s heavy space weather. Though its service was “degraded” during the storm, its owner Elon Musk warned, “All Starlink satellites on-orbit weathered the geomagnetic storm and remain healthy,” SpaceX posted on X.

The more likely outcome of a big solar event could be that satellites’ lifespan is reduced, Lecointe suggests. “A big storm might slow the satellite down, which would require it to use more of its limited fuel supply to get back up to its optimum orbital speed again. Once its fuel is gone then the satellite’s useful life is at an end.”

Not the end of the world

But even if there a huge solar storm were to strike, the space insurance market has the risk under control. “It wouldn’t be an Armageddon scenario for underwriters,” says Lecointe. “It’s something that we consider as part of our realistic disaster scenarios.”

May’s geomagnetic superstorm was tiny compared to 1859’s “the Carrington Event”, and it’s a repeat of that 19th century event which is one of the realistic disaster scenarios that Lloyd’s asks satellite insurers to plan for. Another is a design deficiency that leaves a particular type of geosynchronous satellite vulnerable to solar storm.

Also, despite their complexity, the value of all the satellites insured in space isn’t a huge amount of money, Lecointe adds. Many aren’t insured, either because they are owned by governments or because the private companies that operate them didn’t buy cover for them. “The total value of insured assets out in space is around $25 billion, which is the equivalent of a medium-sized hurricane.”

Furthermore, not all satellites would be lost in a major solar storm, as only those that are between the Sun and the Earth when a solar flare or CME reaches our planet that would be in the firing line. “So, a major solar storm would result in a loss, but a manageable loss, and the capital allocated to this class of business takes that into consideration, as a major solar storm would be a one-in-100-year event,” Lecointe states.

“So, a major solar storm would result in a loss, but a manageable loss, and the capital allocated to this class of business takes that into consideration, as a major solar storm would be a one-in-100-year event,” Lecointe states.

So, we can enjoy the memorable lightshows conjured up by the immense power of the Sun safe in the knowledge that if a huge solar storm were to hit, it wouldn’t cost the Earth.